From struggling brands to parallel exports — how China’s cars are reaching markets worldwid

Neta, a medium-sized electric vehicle startup once seen as a contender in China’s EV boom, is now staggering under the weight of RMB 10 billion in debt (about AUD 2.1 billion). With 2024 sales falling by nearly 50% year-on-year to just 64,500 units, and domestic momentum drying up, the brand’s future is uncertain.

Neta’s investor Zhou Hongyi has shown growing concern over the brand’s direction. Last year, the tech billionaire publicly criticised Neta's product naming and marketing strategy, questioning whether the company had a clear vision. Meanwhile, former CEO Zhang Yong’s recent trip to the UK — reportedly to raise capital — has sparked speculation that he may be on the run (跑路).

But while the brand falters at home, half of its vehicles in 2024 were sold overseas, in markets such as Indonesia, Central and South America, and Southeast Asia. Neta has boasted ambitions to expand into 184 international markets. In some ways, Neta’s global push is a desperate survival tactic. In others, it reflects a broader truth: China’s vehicle exports — both EV and petrol — are reaching markets worldwide.

Two Channels: OEM Ambitions and Parallel Export Surges

China’s rise as a global auto exporter isn’t led by a single strategy — it’s powered by two parallel forces.

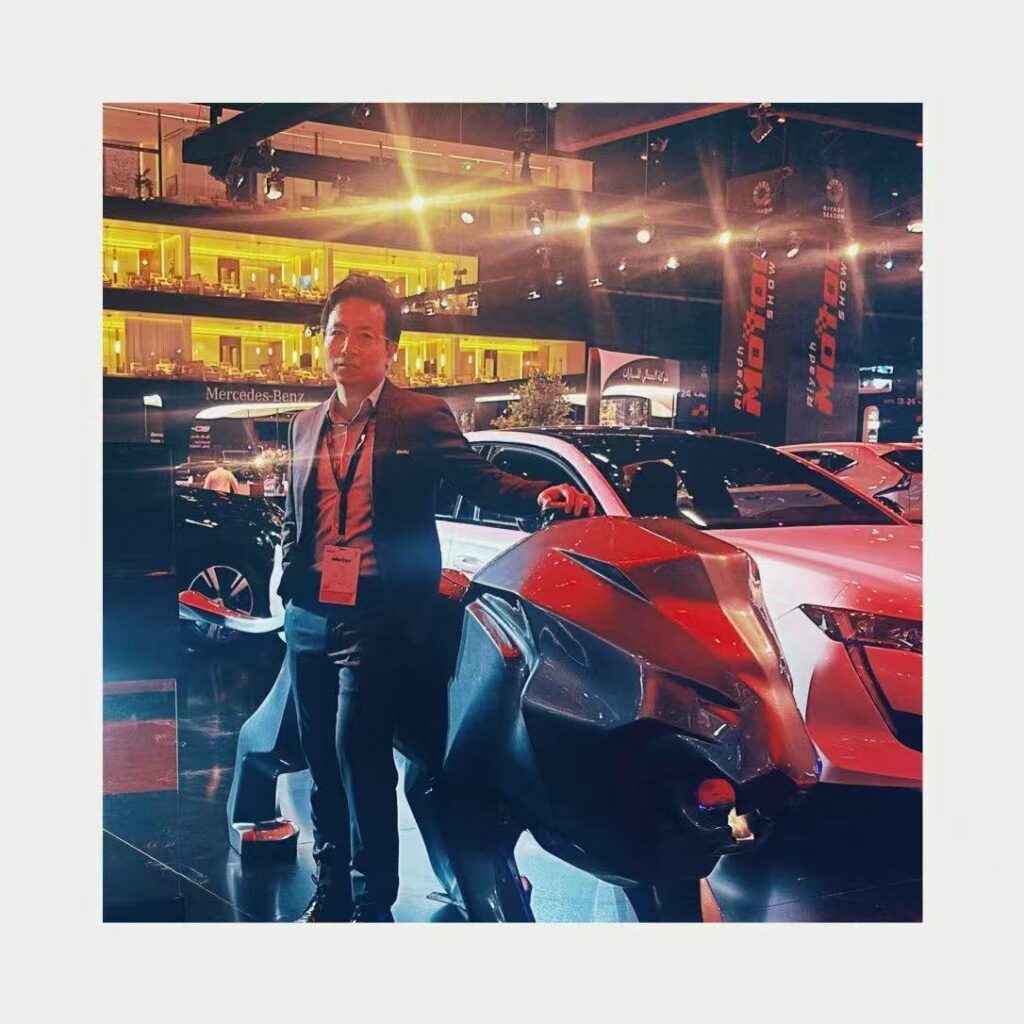

What follows are insights drawn from my own professional experience between 2023 and 2024. During this period, I led a business division focused on exporting vehicles for a Chinese dealership group. My role spanned from assisting the company in applying for official export permits to connecting with buyers around the world through both digital platforms and in-person outreach. This hands-on involvement gave me a close-up view of how China’s vehicle export strategies work in practice — from structured OEM rollouts to the nimble, trader-driven networks driving global distribution.

1. OEM-Led Expansion

Major manufacturers like BYD, Geely, and Chery as well as EV brand such as Xpeng have embarked on comprehensive international strategies. These firms are building factories in Thailand and Mexico, forming joint ventures in the Middle East and Latin America, and rolling out EVs designed for global compliance. Their approach mimics the rise of Japanese and Korean carmakers — slow, strategic, and infrastructure-heavy.

GWM, formerly known as Great Wall Motors, has been in the Australian market since 2009. In 2024, it finally broke into the top ten automotive brands in Australia, delivering over 40,000 vehicles, mostly petrol-powered SUVs and utes. Rather than an overnight success, this milestone reflects what the company describes as a long-term strategic approach — a commitment to “长期主义”, or playing the long game in overseas markets.

2. Trader-Driven Exports

Running in parallel is a more informal but fast-growing channel — one powered by dealers and independent exporters, selling mainly left-hand drive cars into regions like Africa, Central Asia, and South America. These exporters rely on bulk sales of both new and used vehicles, targeting markets where regulations are looser and price sensitivity is high.

These exporters, dealing primarily in left-hand drive vehicles, focus on bulk sales of both new and used cars — including joint-venture models such as GAC Toyota and SAIC-VW, alongside emerging Chinese EV brands. Their key destinations include Africa, Central Asia, and South America, with vehicles typically shipped either in containers or via roll-on/roll-off (Ro-Ro) vessels, depending on cost and logistics.

Exporters in this segment typically operate under the used car export permit (二手车出口资质), issued by China’s Ministry of Commerce. However, many of the so-called “used” vehicles are, in fact, brand-new cars that have been briefly registered and then deregistered. This administrative workaround allows the vehicles to qualify as “used” under export regulations.

At the same time, China’s automobile overcapacity has likely intensified the outbound push. In August 2023, only 402 businesses were licensed to export used vehicles; by 2024, that number had surged to nearly 3,000. Among them are local dealerships that have struggled with sluggish domestic sales and turned to exports as an alternative revenue stream.

A Growing Footprint in Russia and Central Asia

Among the most active regions in this global flow are Russia and Central Asia, where geopolitical and economic shifts have created an opening for Chinese vehicles to dominate. Deliveries to these markets are often made by rail, using routes such as the China–Europe Railway Express or passing through key inland ports like Horgos.

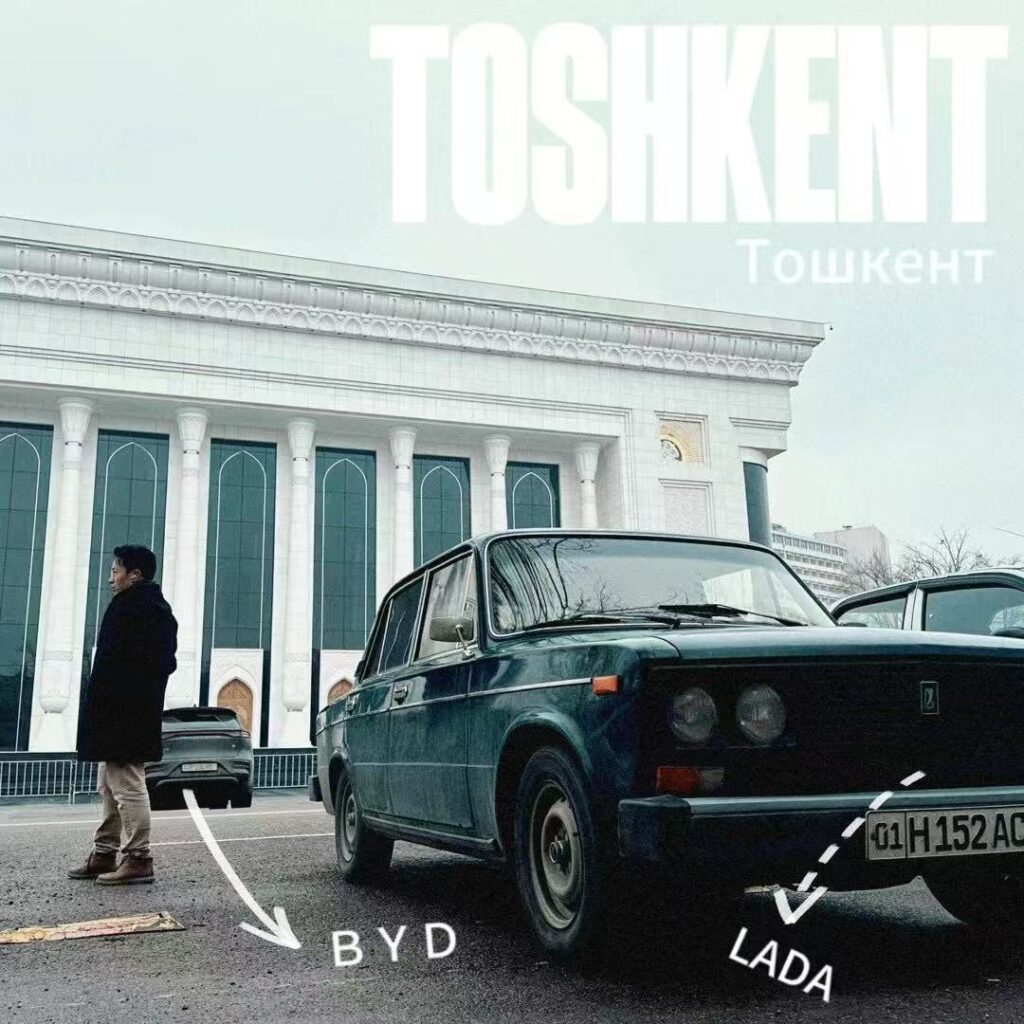

In Uzbekistan and neighbouring countries, the trend is equally clear — both as growing consumer markets and as transit routes for vehicles en route to Russia. Chinese vehicles — especially EVs and mid-sized SUVs — have surged in popularity in Uzbekistan. Paralle-imported Leapmotor and Li Auto are gaining traction in this Chevrolet-dominated market, even without an official OEM presence.

But these markets are not without barriers. Governments regularly adjust customs policies to manage the volume and type of incoming cars. Uzbekistan has introduced multiple new clearance rules in recent years — sometimes tightening standards, other times adjusting quotas to regulate the volume of grey imports. Another market shaped by geopolitical complexities is Iran, where joint-venture Toyotas and Chinese-made Mercedes-Benz vehicles have begun entering the market — despite the country remaining under international sanctions.

How International Traders Source Cars from China

Behind this surge in exports lies an ecosystem of global importers and traders, sourcing vehicles through a mix of online platforms, international trade fairs, and in-person visits.

1. Online B2B Platforms

Platforms like Made-in-China.com have become key entry points for global buyers. With a history nearly as long as Alibaba, the site offers thousands of car listings — although often plagued by duplicate entries, inconsistent specifications, and unreliable pricing.

To improve buyer confidence, Made-in-China works with third-party agencies to verify business registration and operational legitimacy. Verified businesses are given the "Audited Supplier" badge, signalling a minimum level of trustworthiness and transparency in a still-fragmented marketplace.

In recent years, Made-in-China has also invested heavily in SEO and keyword advertising, helping it attract traffic from a wide range of international markets. The platform’s built-in AI tools and multilingual translation features further support seamless communication between Chinese merchants and overseas buyers — enabling trade conversations across cultural and linguistic boundaries with greater ease.

2. Canton Fair: OEMs and Traders Under One Roof

The Canton Fair continues to be a central event for sourcing Chinese goods — and its automobile section draws a wide spectrum of exporters. Major OEMs use the fair to display their latest models, technologies, and global strategies, while smaller trading companies showcase catalogues of vehicles they can source through factory and dealer partnerships.

For international buyers, it’s one of the few venues where product, pricing, and logistics discussions happen face-to-face, often setting the foundation for long-term sourcing relationships.

3. Spot Purchase Model: Buy Direct from the Dealership

Finally, many buyers — particularly those from emerging markets — still rely on the spot purchase model. They travel to China, visit dealerships, inspect available inventory, and pay USD in cash for purchase and export.

This model is especially popular for buyers seeking new or used vehicles, minibuses, and stock petrol SUVs — where time-to-market matters more than branding or factory orders. It offers speed, flexibility, and often lower pricing — although it comes with challenges around consistency, after-sales support, and parts availability.

Final Thoughts

China’s vehicle export wave is no longer just about excess inventory or short-term opportunism — it’s a sign of deep structural change in the global automotive landscape. Chinese brands are expanding and growing at a pace that outstrips the rise of Japanese and Korean automakers in earlier decades, driven by both state-backed scale and private-sector innovation.

One of the most telling signs of this shift is that consumers in many regions are now willing to import Chinese EVs even without local OEM support — reflecting not only growing confidence in their quality, but also a shifting perception of EVs themselves, which generally require less frequent servicing than petrol cars.

It’s not just about ambition either — Chinese EVs now lead in key areas like battery technology, driving range, and smart features. Whether it’s the affordability of a Leapmotor, the performance of a Xiaomi SU7, or the off-road luxury of a Yangwang U8, these vehicles are redefining what’s possible within their price segments.

Even in heavily protected markets like the U.S. and Canada, where high tariffs keep Chinese cars officially out, there is growing consumer awareness — and even demand. Enthusiasts are already exploring import workarounds, curious about what they’re missing in terms of speed, tech, and value.

While more Chinese EV brands are expected to collapse in the near future, the global flow of Chinese vehicles is not just wide — it’s fast, strategic, and increasingly powered by product strength.

And for those of us watching from within the industry, we can’t help but wonder: Is this only the beginning? If you're interested in learning more or exchanging insights on Chinese car exports, feel free to reach out via email.